Swipe For More >

Sorghum Exports to India Will Require Patience and Presence

When sorghum farmers look to markets beyond our borders, China is the first that comes to mind – and for good reason. But robust market development is about looking far down the road, and for that, the industry is turning to one of China’s neighbors: India.

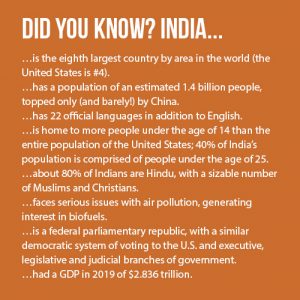

India is a country with just over one-third the land area of the United States and 1.4 billion people, a population expected to soon overtake China’s as the largest in the world. It is incredibly diverse internally, the result of a history of many cultures melting on the subcontinent for millennia. It’s a country in which half the population is engaged in agriculture, often as small holders, subsistence farmers, and that has a notably protectionist and complicated trade policy approach.

And, India knows sorghum. The country is both a large producer and consumer of the grain, ranked #6 for each in the world on a five-year average basis. The country holds large ending stocks, the third highest in the world after the United States and Argentina.

On the plus side for potential future imports of U.S. sorghum, India has a huge and growing population that wants higher-quality food. The country is a robust starch market that wants non-GMO products. The Indian government has called for meeting an E20 standard by 2025, a goal aimed at mitigating emissions and supporting local farmers but one that is pressuring grain supplies that will lead to major deficits.

The challenges: the current tariff on U.S. sorghum is 50%, and despite many years of work by National Sorghum Producers and others to achieve it, there’s not a pest risk assessment (PRA) in place to pave the way for imports. India is committed to self-sufficiency throughout its economy. The large rural vote gives agricultural interests enormous power.

Shelee Padgett, the Sorghum Checkoff’s director of emerging markets and grower leader development, said the sorghum industry has kept an eye on India for 15 years as part of its broader strategic approach. Now, she said, she senses new momentum despite the barriers. There’s a new U.S. ambassador in Delhi, and the U.S. Grains Council, the overseas market development organization for sorghum and other feed grains, recently opened an office in the capital city, the first and only of its kind for a U.S. agriculture promotion organization at this time.

“What excites me the most is the population in India is exploding so much that at some point in time, they’re going to need our grain, and there are some small wins that I think sorghum could easily capture,” she said. “Is it going to be easy? Heck no.”

Reece Cannady, U.S. Grains Council director for South Asia, who lives and works in Delhi, also emphasized the potential for grains over the long term—and also the patience in the meantime.

In a country of diets that are very grain-based, Cannady noted that sorghum is a traditional food and is often incorporated in changing diets that include more products like protein bars. He noted the United Nations declared 2023 the International Year of the Millet, a celebration India takes seriously with displays and educational campaigns.

Padgett said she sees the most potential near-term in starch, followed by food uses, followed by grains—all a long way off from sales and shipments. Step one is to provide information about the product.

Padgett said she sees the most potential near-term in starch, followed by food uses, followed by grains—all a long way off from sales and shipments. Step one is to provide information about the product.

“The U.S. does grow varieties that India does not have access to. Currently, the sorghum they’re growing is higher tannin, which does not provide the same nutrition. There’s interest in these specialty products that the U.S. can use to differentiate itself,” Cannady said.

Verity Ulibarri, vice chairwoman of the U.S. Grains Council and a representative from the Sorghum Checkoff, visited India in early 2023 to mark the opening of the Council’s office there.

“The main takeaway that was evident to me was the importance of a physical presence and how vital that is there to prove that we are serious about working with them,” she said.

Ulibarri drew a line from these efforts over the long term to increased stability and value for U.S. producers.

“It is important to further develop this market in order to create a greater demand pull and competition for sorghum and co-products. This will not happen overnight,” Ulibarri said.

Dale Artho, a sorghum farmer in Wildorado, Texas, has worked in and around trade policy since taking a trade policy class sponsored by NSP in 1994. He is a past chairman of the Council and served for more than two decades on USDA’s agriculture trade and policy advisory committees.

His analysis of India’s future potential is borne of the experience of seeing trade negotiators in action and the dramatic changes in his area after the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect in the mid-1990s. He concluded that the extent to which India becomes a market for U.S. sorghum, or other grains, will depend on geopolitics and the country’s push for self-sufficiency, not unlike China.

“With the dietary needs of India today, there’s a place for sorghum, there’s probably a really good place for it. But depending on how Westernized diets become, that will be the long-term story,” he said.

Like all markets, Artho said Indians want their children to have better than themselves, and, like in all markets, the market share hinges on a product customers want to buy.

“Having been in over 40 countries, people that I meet, interact with and talk with, they all have similar goals to what I have,” he said. “Sometimes that desire of parents to raise the living standard of their children is tied directly to trade.”

A delegation from the Sorghum Checkoff will visit India in January to learn more about the country, and market, and discover what levers there are to pull in the short-term that will pay off in the years and decades to come.

“All of the macroeconomic factors are pointing to: you need to be here,” Cannady said. “And, this market will require more patience than likely any other market we deal in. We were in China for many years before it started to take off. If you’re not here to do the leg work and trudge through the mud you need to trudge through, it won’t ever happen.”

Artho’s message for his fellow farmers is similar—and as relevant to India as it was to China and will be to other markets down the road.

“There’s hope. There’s a lot of hope and a tremendous amount of opportunity to partner with India for selling sorghum into that market.”

###

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2023 Issue of Sorghum Grower magazine.