Swipe For More >

Will Farms Follow Merger & Acquisition Model?

A look into at strategic partnerships as an opportunity to increase viability. A look into five considerations behind farmer mergers and acquisitions and other strategic partnerships.

The pace of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in the agricultural retail space since the U.S. farm economy started its current nosedive has been staggering. From DuPont and Dow to Bayer and Monsanto, already gigantic companies have found it difficult to operate at their historical size—or have seen opportunity for even better profit margins in light of opponents’ stress. With financial stress on the farm even higher in many cases, will farmers be next?

Farmer M&A is a difficult subject since a necessary component of the discussion deals with farm businesses—often family farm businesses—being restructured or even dissolved. However, there are legitimate gains to be made from some amount of consolidation, and complete loss of control over an enterprise is not always a foregone conclusion in these situations. In fact, farmers should look at strategic partnership as an opportunity to increase viability instead of seeing it as a move only forced by a lender or made as a last-ditch effort to stave off financial ruin. Following are the top five considerations behind farmer M&A or other strategic partnerships.

#1: More Favorable Access to Capital

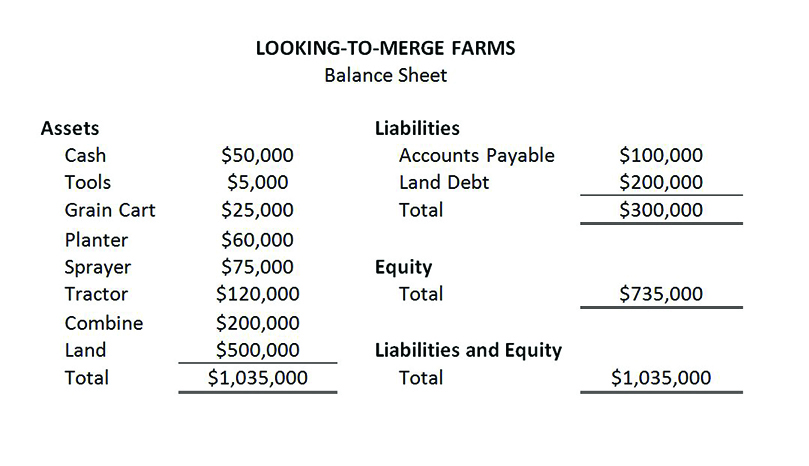

Most farmers partner to lower costs or add value. However, many farm balance sheets could gain considerable strength with the right merger activity. Consider the example balance sheet of Looking-to-Merge Farms in Figure 1. With a moderately strong balance sheet, annual revenues of $332,500 from 87,500 bushels of sorghum and $272,598 in total costs, this operation has an equity-to-asset ratio of 71 percent (indicating stable to strong solvency), a current ratio of 0.50 (indicating very weak liquidity) and a long-term debt coverage ratio of 135 percent (indicating stable to strong ability to repay debt). However, at just 700 acres, Looking-to-Merge Farms will soon be too small for its area. In addition to excess labor capacity, the farm’s accounts payable includes a payment of $25,000 for a combine sitting idle for all but a couple weeks out of each year.

Fortunately for Looking-to-Merge Farms, the neighboring farm (already a partner in a side cattle enterprise) is a near-mirror image in size and financial position, so the two decide to join forces. They sell all but one set of equipment—generating $485,000 in cash and eliminating the $25,000 combine payment—and use $100,000 to lower the combined entity’s total land debt as well as restructure the note. Ignoring taxes and transaction costs, the new entity, Strong Farms, has $1.87 million in assets, $300,000 in land debt, a 76 percent equity-to-asset ratio (indicating strong solvency), a current ratio of 2.77 (indicating extremely strong liquidity) and a long-term debt coverage ratio of 1,337 percent (indicating extremely strong ability to repay debt). Lenders now compete to finance Strong Farms.

#2: Reduced Labor Cost

Conventional wisdom in the general labor force holds farm jobs pay poorly, but most farmers disagree. Although hourly wages may not be competitive, when other paid expenses are quantified, farm workers are often compensated well. For example, many farmers pay for a side of beef (worth approximately $1,500), rent (worth approximately $750 per month), utilities (worth approximately $200 per month), insurance (worth approximately $1,800 per year), a vehicle (worth approximately $6,000 per year) and a gas allowance (worth approximately $100 per month). All told, this is $21,900 worth of compensation. When added to a yearly salary of $35,000, this amount brings total compensation to $56,900 or 42 percent higher than the 2016 U.S. median pre-tax individual income of $40,078. For Strong Farms, reducing labor costs by the equivalent of one full-time worker means savings of $40.64 per acre.

#3: Increased Management Proficiency

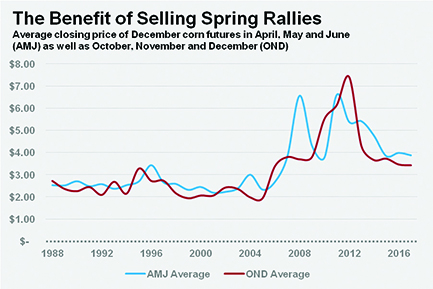

In a time when economic and technological complexity as well as the size and scope of farm businesses are increasing almost as rapidly as costs, more and more, farmers need specialized knowledge and focus. While this fact means eschewing the jack-of-all-trades moniker, farmers who focus on one aspect of their business and acquire the rest through M&A—just as seed companies have acquired coveted genetics—could see exponential productivity growth. For example, prior to the merger, Looking-to-Merge Farms managed all aspects of the enterprise internally, and this meant marketing often took a back seat to ensuring a successful year agronomically. Figure 2 quantifies the opportunity cost of not marketing. Over the past three decades, the average closing price of December corn futures in April, May and June has been $0.21 higher than the average closing price of the same contract in October, November and December. With total production of 175,000 bushels, capturing this difference is worth $36,750 to Strong Farms.

#4: Increased Equipment Efficiency

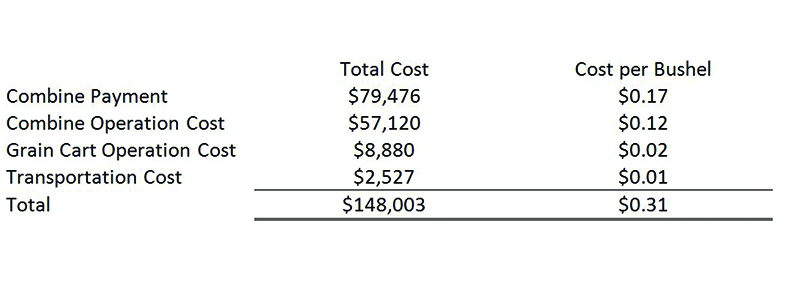

Looking-to-Merge Farms understood the problem with excess equipment capacity and remedied the situation by doubling the amount of acres covered by a single piece of equipment. Could this concept be expanded? Figure 3 details total costs for a new combine (traded annually) that approximately follows harvest northward, cutting sorghum for partnering businesses—each supplying a grain cart at their farm—in South Texas, then Oklahoma, then north central Kansas. Conservatively assuming the combine cuts 480,000 bushels (6,000 acres at 80 bushels per acre) throughout the summer and fall, the harvest cost for each partner is $0.31 per bushel. Accordingly, this partnership offers significant savings compared to the average custom rate across much of the Sorghum Belt of $0.43 per bushel and the pre-merger cost incurred by Looking-to-Merge Farms of $0.37 per bushel.

#5: Increased Bargaining Power

Economies of scale is one of the most well-known and well-understood concepts in economics. After all, thousands of consumers take advantage of ‘buy one, get one free’ sales each year—even each day—and reap the benefits of increased bargaining power. Similarly, enterprises like Strong Farms that find themselves with increased bargaining power due to M&A or other partnerships possess the coveted ability to negotiate. Not only does this lead to potentially higher sorghum prices both in specialty and certain commodity markets, but it gives them the power to negotiate down their input prices, as well.

The Bottom Line

Mergers and acquisitions will not work for every farmer, and businesses exploring partnership options should perform analysis similar to that above and consult with their attorneys, accountants and lenders prior to taking any action. However, M&A have been used to lower costs and improve efficiency almost as long as businesses have been in existence, and farmers may soon look more often at strategic partnerships as opportunities instead of threats.