Swipe For More >

Resilient Leadership

With resilience and humble leadership, Oklahoma Panhandle farmer makes his mark on the sorghum industry.

Ken Rose grew up in the Oklahoma Panhandle near Boise City, a booming small town in the early 1900s serving as a hub on the rail line for merchants and traders.

Today, Boise City is a sleepy panhandle town surrounded by farming and grassland in the dry prairie of the High Plains or “no man’s land,” which it is often referred to as. The Dust Bowl of the 1930s left a lasting mark on those who survived it, leaving only a few families, like Ken’s, left to tough out one of the most challenging areas in the west to work and raise a family.

“Those were some really tough years,” Ken said, choking back tears as he recalled growing up in the area forever changed by black clouds of dust. “I went through the ’50s and ’60s, too, with the dust and windy days. There were no crops. My dad went through a number of years with just almost nothing.”

Ken said, growing up, the dust was so bad some days it made it challenging to return home from school.

“The bus would pick us up at school then drive to the edge of town, and the dust would be so bad he’d just turn around and take us back,” he said. “He’d drop us off at a friend’s house in town, and in the evening when the wind went down and folks could see to drive on the highway, they’d come in and pick us up.”

These tough times prompted Ken’s father to encourage him to pursue an education and profession away from the farm.

“I remember dad saying, ‘Son, I want you to go to college and get yourself an education, and go find a good job,’” he said.

And so he did.

Ken went to college and received two degrees in chemistry, and over his lifetime he has accumulated over 200 hours of college coursework from six different universities.

“Continual learning and continual education is just an important part of life,” he said.

Ken and his wife Norma made the same emphasis on the importance of education with their two daughters who have secondary degrees, as well.

“Even if you don’t use the education, just the experience of being in college, being confronted with other ideas, other things that are outside of your scope of being on the farm is a good thing,” he said.

Ken spent a number of years utilizing his degrees in the career field working in various places, but through the Holy Spirit and an article in a science magazine about sun spot cycles, he felt a calling home.

“When I was about 33, it just seemed like the Lord was saying, ‘Ok, it’s time to go back to the farm,’” he said.

A common belief about the sun solar cycle is the sun’s magnetic field goes through a cycle approximately every 11 years. Ken explained there is a deeper cycle every other 11-year cycle with those periods taking place during dust storms both in the 1930s and 1950s. The sun was coming out of the cycle when he returned to the farm, which led to his prediction for a higher rainfall period, and that is exactly what happened, he said.

Returning to the farm, Ken had an eye toward conservation and changing the dynamic of the land once considered cursed.

“I started reading articles about ecofallow—that’s what they called it then,” he said. “It was basically no-till rotations, and I thought, ‘That sounds like something we need to try.’”

Ken attended educational seminars in Kansas and Nebraska to learn what needed to be done to implement the practice on his farm. He was met with resistance.

“The first year I no-tilled wheat stubble and planted milo directly into standing wheat stubble I had neighbors tell me that would never work,” he said. “Now probably 80 percent of the county is doing some kind of a wheat, sorghum, fallow rotation on dryland because it works and saves up soil moisture.”

Ken was a pioneer for no-till systems in his area and took the opportunity to educate other growers in the county through his service on the local conservation district board. Sitting on top of the Ogallala Aquifer, Ken also recognized the limited asset farmers have and encouraged farmers to limit their water use and utilize crops and practices that provide the best benefit. Insert sorghum.

“I look at sorghum as the drought buster or the thing that has probably made my farm as profitable as anything,” Ken said about sorghum in his rotation.

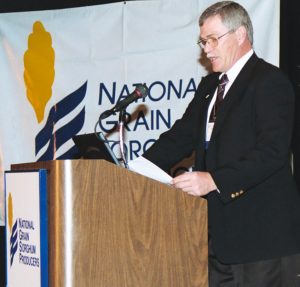

Ken’s passion for sorghum on the farm led to his leadership for the industry on both the Oklahoma sorghum and National Sorghum Producers boards.

Ken’s passion for sorghum on the farm led to his leadership for the industry on both the Oklahoma sorghum and National Sorghum Producers boards.

Ken said, at the time, Mabry Foreman, the longest sitting chairman and founding board member of NSP who served close to 40 years, was considered Mr. Sorghum and had a lasting impact on Ken and his leadership journey.

“Mabry was very direct about how much we needed to have a voice in politics and up to that point, I hadn’t really thought about politics or the political side of farming and raising crops,” Ken said. “Mabry was emphatic about how farmers need to get involved and realize the power they have in state and national government. That had a huge impact on me.”

Ken said serving on various boards was difficult at times but made him better at home. From increasing international markets to setting strategies to develop a national sorghum checkoff board, Ken has seen a lot of changes in the sorghum industry and is considered one of the sorghum greats, serving as NSP chairman from 2002-2003.

He humbly credited the influence of other past sorghum leaders like Bill Kubecka, Dale Artho, Stan Fury and Terry Swanson in addition to Mabry along with the leadership of NSP CEO Tim Lust.

Today, Ken is transitioning his farm ground and equipment to his long-time hired hand while retaining his cow herd. He said he looks forward to time spent with his family in Red River, New Mexico, feeding milo to the deer and chipmunks.

He said in spite of the ups and downs, the Lord has been good to him and his family and they have been blessed. Adding to his list of life influences, Ken remembered his father.

“Without a doubt, my dad has been very influential as far as being able to survive on a difficult farm in a difficult area.”

Ken just completed 11 weeks of radiation, diagnosed with prostate cancer earlier this year, but the prognosis is good, and he is home doing well. A resilient man and humble leader, Ken Rose, National Sorghum Producers and Oklahoma Sorghum thank you for your leadership.

###

This story originally appeared in the Summer 2020 Issue of Sorghum Grower magazine as a feature.