Swipe For More >

Capturing the Benefits of USDA Programs

From farmers, to bankers, to input suppliers, to small rural businesses, everyone involved in agriculture needs the added level of financial certainty farm programs provide. National Sorghum Producers is here to help producers with existing programs and constantly on the lookout for opportunities afforded by new programs or programs they are not currently using.

For many years—decades, even—farm program payments made up a significant portion of income for some farmers. For a time, direct payments were guaranteed by statute, and countercyclical payments were all but assured as commodity prices sputtered along and perpetually threatened to test multi-year lows. Add to those programs the occasional disaster payment, and U.S. farmers could predictably rely on farm programs to help remove some level of catastrophic risk.

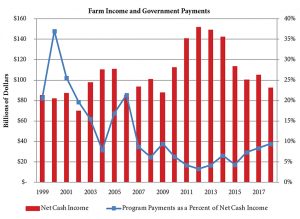

From farmers, to bankers, to input suppliers, to small rural businesses, everyone involved in agriculture needs the added level of financial certainty farm programs provide. Unfortunately, while net cash income for U.S. agriculture has declined a staggering 37 percent from its 2012 high, farm bill program payments as a percent of that income have not increased in proportion to the loss. Figure 1 illustrates this unsettling financial reality.

With payments from traditional programs down and unlikely to recover anytime soon (for most crops—sorghum is the lone exception given its strong $3.95 reference price), farmers need to be mindful of how they are using existing programs and constantly on the lookout for opportunities afforded by new programs or programs they are not currently using. While there are dozens of considerations for existing and new program use, three of the most important programs relate to conservation programs, entity structure and beginning farmer and rancher benefits.

Conservation Programs

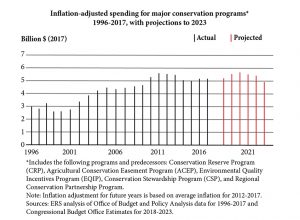

Funding for conservation programs has steadily increased over the past couple decades with current spending levels approaching $6 billion (see Figure 2). The most common conservation program is the

Conservation Reserve Program, but the most beneficial programs for sorghum farmers are working lands programs like the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) and the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). CSP incentivizes conservation practices adopted across whole farms under multi-year contracts, while EQIP lives up to its name by equipping farmers—typically at the individual field level—with resource-conserving technology aimed at driving positive conservation outcomes.

Many sorghum farmers have utilized CSP and EQIP, but some do not realize the full scope of these programs. The USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) relies on 169 conservation practice standards to design the incentives available under CSP and EQIP, so there may be opportunities in areas many farmers have not considered. A few current examples include incentives related to soil properties, drainage and irrigation efficiency in addition to upcoming incentives related to resource-conserving crop rotations, which National Sorghum Producers worked to secure in the last two farm bills.

Entity Structure

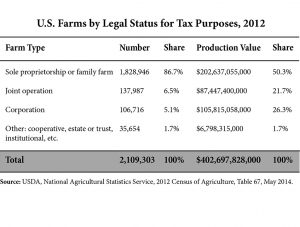

Perhaps the most expensive mistake farmers can make when enrolling in farm programs is failing to structure their entities in a way that enables the receipt of payments that commensurate with actual financial risk (see Figure 3). For sole proprietorships, payment

limits for crops, other than peanuts, are a combined $125,000 for each individual associated with the principal operator under the Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) and Price Loss Coverage (PLC) programs, reduced by any sequestration. The key here is an individual associated with the principle operator includes a farmer’s spouse, so the common husband-wife farming duo effectively has a limit of $250,000. With updated program yields and the large price losses experienced over the past few years, such a payment only requires a few thousand acres in some areas. Joint operations are similar in that each member in the operation has a separate limit.

The exception is corporations, which have a single limit of $125,000 regardless of the number of members. While this single limit is seen by many as a rule that protects family farmers from encroachment by corporate agriculture, it is important to remember a corporate structure is used by many family farmers for legitimate tax, liability and other reasons. For any farmers—incorporated or not—who have questions about entity structure or are interested in restructuring, NSP is always happy to help. There is also a wealth of knowledge in this area among private consultants. One such consultant is Performance Agriculture Services, who can be reached by visiting farm-consultants.com.

Beginning Farmer and Rancher Benefits

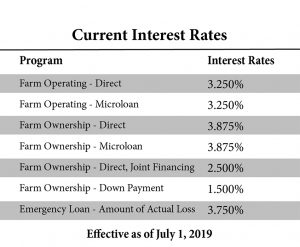

Beginning farmer programs are an important part of many young farmers’ businesses, and these programs received a boost under the 2018 Farm Bill. Not only were funding levels increased, the programs were expanded to include veterans and other socially disadvantaged and historically underserved groups. For USDA Farm Service Agency programs, beginning farmers are defined as farmers in their first 10 years of operation. While there are multiple benefits for beginning farmers, including higher subsidy rates for crop insurance, the most significant are the interest rates (see Figure 4).

In conclusion, farming comes with an inordinate amount of risk—regardless of the size of farms. For almost a century, the U.S. government has considered agricultural risk a strategic threat to the safety and economic viability of the country and has funded programs to help farmers manage these risks. However, traditional farm program payments have declined significantly in recent years, so farmers must pay close attention to existing programs and constantly look for opportunities afforded by new and underutilized programs.

###

This story originally appeared in the Summer 2019 Issue of Sorghum Grower magazine in the Sorgonomics department.