Swipe For More >

Ethanol Fueling Export Markets Around the World

While the ethanol industry is facing challenges today as a result of the Russia-Saudi Arabia oil price war coupled with lower gasoline consumption due to the COVID-19 pandemic, historical demand for U.S. ethanol around the world has continued to grow.

While the ethanol industry is facing challenges today as a result of the Russia-Saudi Arabia oil price war coupled with lower gasoline consumption due to the COVID-19 pandemic, historical demand for U.S. ethanol around the world has continued to grow.

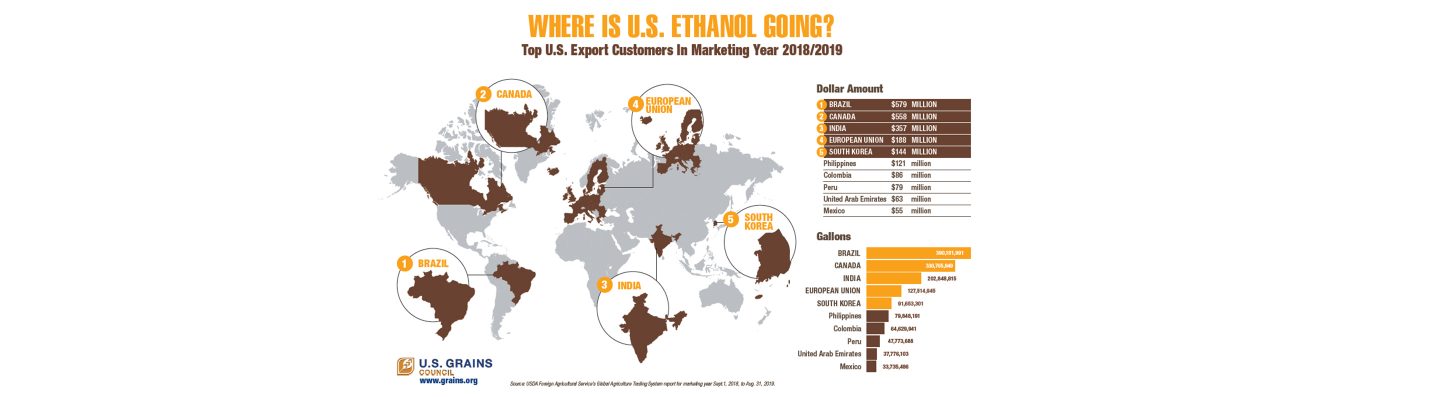

Ethanol exports reached new heights in 2018 with the U.S. shipping almost 1.7 billion gallons to 74 countries, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service. Last year, U.S. ethanol exports were 1.47 billion gallons with total production at 15.7 billion gallons, consuming 517 million bushels of grain and contributing to approximately 21,000 American jobs.

Seeking Demand Outside the U.S.

The pathway to these export levels was made possible when ethanol proponents began looking outside U.S. borders and engaging on both domestic and global trade policies, according to Brian Healy, director of global ethanol development for the U.S. Grains Council. He said the U.S. was, at that time, ramping up ethanol production from 2007 to 2010, and imports of ethanol from Brazil were used to backfill demand.

“There was recognition from the U.S. industry that there was a growth opportunity in foreign markets ethanol could service,” Healy said. “Growth outside the U.S. could further support U.S. feedstock producers here for corn, and sorghum, as well.”

Craig Willis, Growth Energy’s senior vice president of global markets, said, worldwide, the average blend rate is around 7 percent ethanol in the gasoline pool. If you take the U.S. and Brazil out of the equation, he said that rate drops to a little over 1 percent.

“We’d like to get E10 throughout the entire gasoline pool,” he said. “That would mean 20+ billion gallons of potential market development opportunities. “We don’t expect to open this much demand overnight. However, opening just one key market such as Indonesia could create more than a billion gallons of new ethanol demand, or 350 million bushels of new grain demand.”

The U.S. exports approximately 10 percent of what is produced with the majority of ethanol exports going to countries like Brazil and Canada, but countries like Mexico and China offer considerable opportunity. Willis said if Mexico can convert to an E10 blend fuel, the country has a potential 1.2 billion gallon market for U.S. ethanol producers.

“There is a huge potential for new demand there,” he said, “so we are spending a lot of time both on the policy side and on the market development side, as well.”

Massive Opportunity in China

Both Healy and Willis agree the big market opportunity is China.

“If there was any market on the planet that could move the bottom line of ethanol producers and their customers and stakeholders the fastest, it would be China,” Willis said. “They are embracing ethanol going forward and, today, blend at about a little over 2 percent countrywide.”

Willis said China had a 2017 policy to reach E10 blends across the country by 2020. While some provinces have embraced E10, fulfilling the mandate to use a blend of 10 percent ethanol and 90 percent gasoline (E10) by 2020 is unlikely as press reports indicate its government has slowed this implementation deadline.

“We just got Phase One signed January 15,” he said. “Of course, the coronavirus situation is going on right now, but, hopefully, once we get back to normalized trade, ethanol can be one of the big winners.”

Other challenges exist with China, as well. China currently imposes a 70 percent cumulative duty on U.S. ethanol.

In addition to fuel, Chinese demand for ethanol coproducts such as dried distillers grains with solubles (DDGS) is potentially significant, as well, and this makes the overall opportunity with China even larger. If margins line up once again for ethanol and DDGS, Healy says China could easily import a billion gallons of ethanol in the future.

Low-Carbon Markets Offer Premium

Another opportunity specific to sorghum, Healy said, is carbon sensitive markets.

“There are certain markets where carbon intensity is the most important metric and where a premium can be realized,” he said. “Globally, the world is moving in a direction where there is more incentive to have lower carbon intensity ethanol, and some sorghum plants do have an advantage in terms of carbon intensity reduction.”

“If the premium is going to be there,” Healy said, “it’s going to incentivize greater production of sorghum-based ethanol.”

Most sorghum farmers are aware of California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) and its impact on sorghum ethanol plants, but other fuel markets requiring producers to provide sustainability data are rapidly proliferating. Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, the European Union and Japan are just a few examples of countries or regions with low carbon fuel markets similar to the California LCFS.

Present Day Challenges

Ethanol exports have been setting records the past few years, but, at the time of writing, current conditions associated with COVID-19 could hamper domestic production. Fewer people on the road means less demand, and gasoline prices continue to drop.

While a number of ethanol plants are considering temporarily shutting down, fortunately, managers of plants with physical ownership of sorghum were able to sell sorghum stocks back to companies like ADM and Cargill who are taking advantage of renewed demand in the sorghum export market to China.

These are serious challenges, but ethanol proponents are optimistic the industry outlook improves beyond the year 2020, and building U.S. ethanol export demand across the world remains a critical priority.

###

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2020 Issue of Sorghum Grower magazine in the Sorghum Markets department.